The Dostoevsky Lens: Mapping the Terrain of Inner Conflict

“Patients,” Power, and the Clockmaker’s Universe

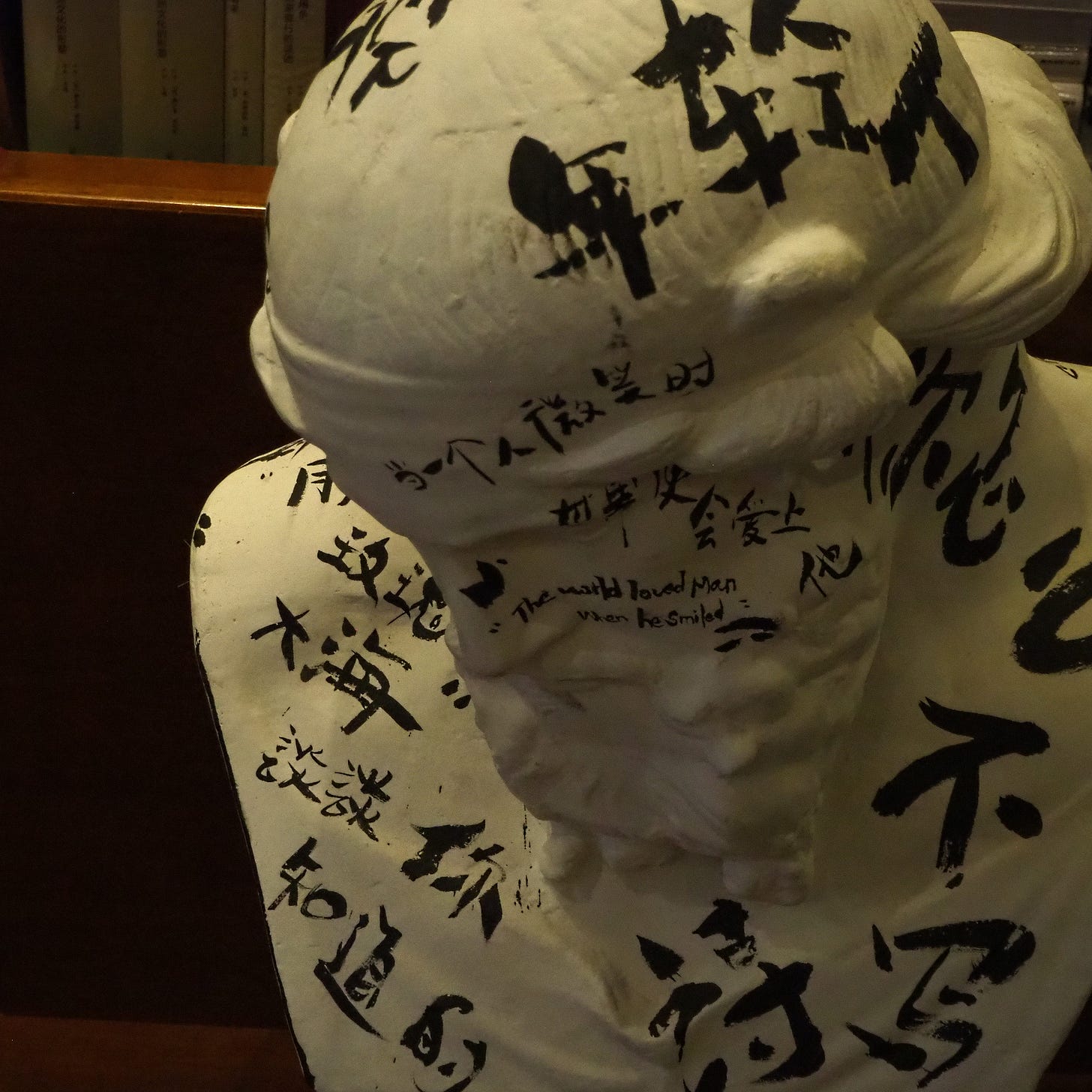

Reading Dostoevsky often feels like gossiping across time, yet also like stepping into a psychological laboratory.

His characters are not just figures on a page—they are magnified souls: frenzied, stubborn, full of contradictions, yet in key moments they suddenly seize the hearts of ordinary readers, forcing them to confront the weaknesses of human nature.

—

1. The “Patients”

Dostoevsky’s works are full of what I call “patients.” On the surface, they appear ordinary, but within, they harbor obsessive fantasies and beliefs that are incomprehensible to others yet impossible for them to relinquish.

His portrayals are so incisive that carefully reading the inner worlds of these “patients” makes one empathize with their choices and circumstances. They are sensitive, obsessive, stubborn to the extreme, yet alive in a way that makes a reader, dulled by the routine of daily life, feel a sudden chill in the face of their gaze—if I were them, what would I do?

Dostoevsky’s pen is like a scalpel, slicing open these souls and forcing readers to confront their twisted helplessness and fragile struggles. Perhaps everyone harbors a “patient” within, but most are too busy surviving to pause and examine their inner selves.

Among the Dostoevsky I’ve read, the most typical “patient” is the narrator of Notes from Underground. His mind is frenzied, his speech daring. When I first opened the book, I unconsciously framed him with a layer of prejudice, trying to judge his madness and provocation from a moral high ground. But as the narrative unfolded, I gradually realized—I had already been persuaded by him.

It turns out I share more in common with the Underground Man than I expected.

This, I think, is Dostoevsky’s brilliance: through extreme “patients,” he forces readers to confront the shadows lurking within themselves.

—

2. The Absence of Women

Yet, while marveling at his exploration of human nature, I often find myself puzzled: why are his female characters so thinly drawn?

In his narratives, women are often trapped within the framework of male evaluation, lacking their own subjectivity. They rarely have the independent conflicts and struggles that “patients” do, and are more often drawn into male-driven narrative logic.

This difference is particularly evident in naming.

Male characters typically have clear societal roles: carpenter, civil servant, policeman, bureaucrat, even the vaguely defined “upper-class man.” Dostoevsky often uses professions to designate them, instantly placing them within a social structure and giving them clear attributes.

Women, however, are different. They are often called “old lady,” “someone’s wife,” “someone’s mistress,” or simply “she.” These designations strip them of subjectivity, making them more like background props filling gaps in dialogue. Those who truly drive intellectual conflict and express sharp ideas are almost always male.

—

3. The Clockmaker’s Universe

Despite this limitation, I cannot help but admire Dostoevsky’s near-magical skill in structuring his works. He links the relationships among characters with incredible precision. On the surface, the cast seems vast and the plot chaotic, almost overwhelming; yet, upon closer reading, there is a hidden order—like a massive clock: gears interlocking, intricately complex, yet running smoothly.

Each of Dostoevsky’s works becomes a small universe. Characters move within it, colliding, restraining, entangling each other, yet collectively maintaining a coherent rhythm. This reminds me of Spinoza, who once described God as a clockmaker. By that analogy, Dostoevsky is both creator and clockmaker of his literary universe.

He constructs characters to the point of near-chaos, yet allows them to achieve inevitable order through their conflicts. That is why Dostoevsky’s world is at once chaotic and clear, oppressive and intensely charged.

—

Epilogue: Reader Participation

Perhaps Dostoevsky’s power lies here: he can dissect individual souls while weaving them into a vast network that operates as a self-sustaining literary universe.

Yet, as we marvel at his “clockmaker” precision, we must not forget that many voices within this universe remain unheard.

So here’s a question for you:

While reading Dostoevsky, have you ever felt persuaded like the Underground Man?

Or have you noticed voices—especially female characters—being overlooked, like silent witnesses to the story?

I’d love to hear your thoughts. Hit reply and share your experience—I’m curious to see what you notice in his universe.